INTRODUCTION

I’m going to discuss here a ‘computer tool’ that people are beginning to find and use. Cousin P. in the midwest, who heads up a charitable organization of Jewish women, told me recently that “I've finally got around to using Chat and it has been mind blowing. If I let it, I could become a writer, lol.“ Cousin M., across the Atlantic, who has a hand in the running of an N.G.O. that works with the U.N., had found Chat and was using it before me. “As you know, I am constantly writing stuff: rhymes, short stories, even novelettes. Now, thanks to Chat, instead of working on them ‘one at a time’, three are always in the air. In addition, Chat helps me implement background (like scenery, etc.) and suggests alternatives as I edit, like dialogue and conflicts that add to the plots tensions.“

Most people will identify this computer tool as ‘AI’. But most people are wrong. This tool is only one *form* of AI; it’s not the whole enchilada. (The meaning of AI — Artificial Intelligence — is so broad and vague that no definition I can give will be any better than what you presently hold.)

These tools are a specific form of AI, and are called ‘chatbots’, a portmanteau word combining chat box and robot. Chatbots are able to communicate in a natural language, assisted by a form of AI technology, described as Large Language Model’s (LLM’s) and other mysterious terms. While chatbots are a specific kind of AI, they are but a very narrow slice.

These chatbots — like Grok, like ChatGPT, like Google’s Gemini and others that are here already or scheduled soon to drop — have been around for about a year. I remember being an early enthusiast.

It’s clear to me now, why initially I went overboard with enthusiasm for chatbots. A chatbot can do two things so impressively that even today, I am often astonished. Firstly, a chatbot is able to communicate with any person in a truly human way. Any chatbot can pass the typical casual ‘Turing Test’. A machine is said to pass the ‘Turing Test’ if the human evaluator, at one end of a communication link, cannot distinguish whether it’s a computer (i.e., a machine), or a human, on the other end of the line. Some holdouts insist that we need to re-define the Turing Test; that more time is needed so that complex reasoning or emotional depth can be better exposed, observed and tested.

A second truly impressive ability is that any chatbot can analyze, organize and categorize massive amounts of material, almost in an instant. The physical analogy is being able to pull together all the available information about a particular topic; including all the many different sets of encyclopedias in the world. Then, having pulled that information together — while everything is being organized, reformatted, polished and packaged for clarity and readability — in the midst of all that, a chatbot prioritizes segments according to ‘importance’. Thus it is able to tailor its reply, slimming it down as necessary to fit into a given allowable space (or the ‘number of words’). These capabilities make any chatbot a truly amazing and fantastic tool.

I thought today I would be appearing before you, carrying a pail of reality to splash on all our chatbot dreams: I was going to tell you that despite our initial enthusiasm we were all going to be disappointed. But I investigated and saw that I already knew that; in fact, it was the message of my first Substack reference to ChatGPT’ in September, 2024.

But psychologically, I now believe that I just couldn’t accept how *bad* these guys performed when faced with simple tasks; compared to how ‘good’ they were in communicating answers and organizing information. When my chatbot worked, it was like having a spell checker on steroids. It’s unbelievable stupidity and failure to learn, just ‘wouldn’t compute’ for me. I naively thought the problem was *me*. I must be making a simple fundamental error in the way I structured my side of the chat. I duly reported on what I found (link above), but basically set my concerns aside.

BAD ADVICE WITH SOME RESULTANT PANIC

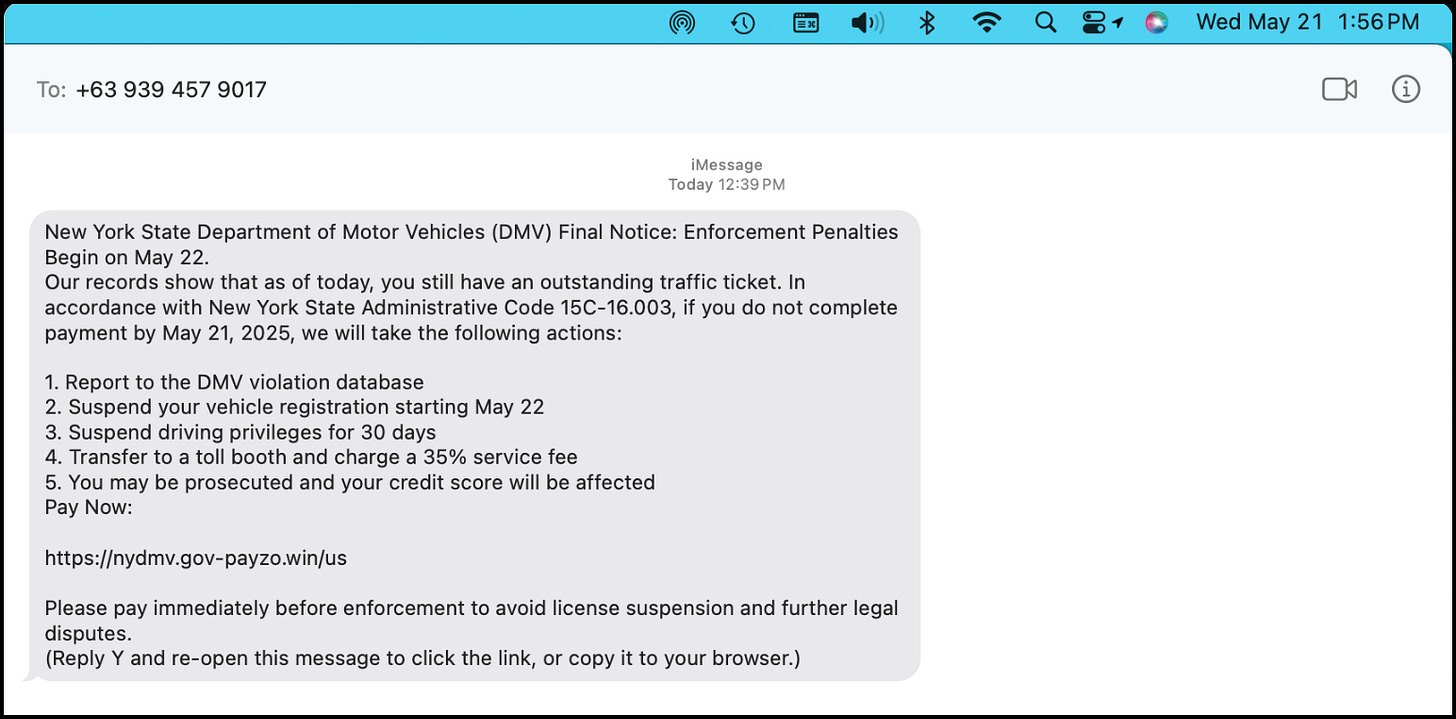

I continued to set aside my concerns, even when the following event occurred. A few months ago, I received a text. I immediately saw it as a clumsy phishing attempt (like from a Nigerian prince), but on a whim sent it to Grok, asking, “Can you read this and advise?”

Grok read it and answered:

Yes, I can read the message. It’s a notice from the New York State Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) stating that you have an outstanding traffic ticket (code 15C-16.003). If you don’t pay by May 21, 2025, the following actions will be taken starting May 22:

1. Report to the DMV violation database.

2. Suspend your vehicle registration.

3. Suspend driving privileges for 30 days.

4. Transfer to a toll booth with a 35% service fee.

5. Potential prosecution and credit score impact.It includes a payment link: http://nydmv.gov-payzo.win/us and advises paying immediately to avoid further issues.

Since today is May 21, 2025, and the deadline mentioned in the notice is also May 21, 2025, you might need to act quickly to avoid the penalties outlined. Would you like advice on how to proceed?

I read Grok with shock and disbelief, which quickly turned to panic! Here I was dismissing this text as an obvious dumb phishing attempt, while Grok, reading the same text, was, in its quiet way, giving it authority, and a sense of authenticity and believability. Confused and uncertain, I was just about to click the link when a cooler form of reason kicked in, and I said to Grok:

Not so fast. What about the email address? It doesn't look like an .gov address that I would expect; it looks more like a .gov approximation. Think Grok. It has to be bogus.

Grok immediately changed its tune:

You're right to be suspicious. The email address in the message uses the domain "nydmv.gov-payzo.win," which is not a legitimate government domain. Official New York State Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) communications would use a ".gov" domain, such as "dmv.ny.gov," as seen in authentic DMV resources. The inclusion of "payzo.win" is a major red flag, as ".win" is not a standard government domain and is often associated with phishing scams. The New York DMV has warned about phishing attempts involving fake links and domains that mimic official ones to steal personal information, often urging recipients to pay fines or provide sensitive data. This message fits that pattern, especially with the urgent tone and threat of penalties, which are common tactics to pressure victims into acting without verifying.

This is almost certainly a scam. Do not click the link or provide any personal information. If you want to confirm the status of any fines, visit the official DMV website directly at dmv.ny.gov or contact them at dmv.sm.phishingattacks@dmv.ny.gov to report the message.

I admonished Grok and it immediately apologized, (something I have found that it’s quite good at doing).

ME: Grok, I'm disappointed that you didn't tell me sooner; but I hope we both learned something.

GROK: I’m sorry for the oversight—I should have flagged the suspicious domain right away. You’re absolutely right to question the legitimacy of that message, and I appreciate your sharp eye in catching the "nydmv.gov-payzo.win" domain as a likely scam. We both learned to double-check domains more thoroughly, especially with something as critical as a DMV notice. Going forward, I’ll be more proactive in spotting red flags like that. If you’d like, I can help you report this to the real New York DMV or suggest steps to protect yourself from similar scams. What would you like to do next?

I never ‘retested’ Grok with another phishing text, so I can’t claim it was lying with its promise to be more proactive, but other indications abound that tell me in situations like this, Grok (and other chatbots) are not to be trusted. They are capable of making errors like this, over and over.

FINDING A WAY TO USE CHATBOTS DESPITE THEIR DRAWBACKS

Despite these warning signs, I continued to use chatbots in the way they are probably best used. Compared to a standard search engine — for example, Google — rather than merely giving you an expanded definition of a term, telling you all about a word or idea that popped into your mind, a chatbot can identify a term or idea that you can’t think about at the moment — a word or concept that *almost* gets to consciousness but stubbornly refuses to reveal itself. In the course of a chat’, a chatbot is able to hunt — not by the word itself, but by ‘associations’ to the word or idea. “No, Grok, that’s not quite it; it’s more like something this… or that…” I’m reminded of a (now dated) spy movie. The chatbot operates like three vans with receivers on their roofs, moving about the city, and by triangulation finding the source of a covert hidden transmission. For seniors, struggling with (normal) ‘word finding’ disabilities, it can be a real boon.

Earlier, I had asked Grok whether it could successfully write ‘code’ for computer programs. (Big mistake. Never ask a chatbot if it can do anything. The answer will always come back, ‘no sweat’, and you will be plunged into hours — maybe days — of wasted effort.) For example, I knew I could save time if I had a small program that would automate some repetitive steps I was taking many times a day. I had to cut out a small patch of screen, showing time and date, then move and paste it onto another image in a slide management application, and bind them together. Grok told me my Mac system had a built in program, called Automator, that would do the trick. Reviews I read said Automator was fussy, sometimes impenetrable and not easy to use. I thought, those earlier reviewers didn’t have Grok at its side, with machetes hacking through the bush. Was I over-optimistically wrong! I wasted a good 12 hours in frustration and failed efforts to get Automator to work.

All of this was in my head when I recently received an email from ‘S.’ S. and I had bonded, almost by accident, discovering that we shared a passion for creating computer programs that could play a standard game of Solitaire. Of course, the main difference between people (us) playing Solitaire and the computer, was that during the time we took to play a single game, the computer could easily play millions. Thus we could take various Solitaire strategies, translate them into computer code, and using large numbers of randomly shuffled games, reliably make comparisons — and determine which strategy produced the best percentage of wins.

S. was a success in his field, not particularly related to computers — knowledgable, respected and widely consulted — yet both he and I shared a portion of our mental apparatus that could only be characterized as your typical ‘computer nerd’. Initially S. told me he could not understand my interest in chatbots, but then he discovered that it could code and write computer programs. I knew he was testing this ability with Google Gemini and I wished him well. He wrote:

I have been having decidedly missed results with Gemini. Repeatedly it has produced, and presented to me with great confidence, code that doesn't work. When I explain the problem (and provide the error message) it repeatedly asserts (again with great confidence) that it understands and has fixed the errors, but again the code doesn't work. Many, but not all, of the problems seem to relate to getting the code to run on my machine (running Windows); so I am setting up a Linux machine to see if Gemini can do any better with Linux. I will keep you posted.

Writing code that works(!) is supremely satisfying to those of us with a mindset that comes with this ‘computer nerd’ function. Getting code to work, after a great deal of effort, can be its own reward. I imagine it’s not dissimilar to what might be experienced by a chess champion or the winner of a cross word puzzle contest. I hope S. will be successful, but I’m not too optimistic.

I’M STILL OPTIMISTIC ON THE FUTURE OF AI IN GENERAL

I hope you’re still holding on to the notion that (a) there is AI and (b) there is a form of AI that we call chatbots. If I say that chatbots will disappoint, I am not predicting that AI will disappoint. I still hold to the idea that AI will revolutionize our life, mostly (but not entirely) for the good.

For example, the recent Park Avenue fatalities underscore the fact the we desperately need a procedure to keep military designed ‘people-killers’, or automatic weapons, out of the hands of anyone who should not own them.1 All of this points up a concern: how can we, as a rational society, keep a gun like this, out of the hands of someone like that? Can we somehow (pragmatically) pass a law that largely bypasses the stringency of the ‘Second Amendment’? How about a law that says all such weapons can be sold but must contain a built-in device that continually sends a signal, indicating where the gun is, at any moment. (Didn’t Israel have something like this in Lebanon?) That’s right, we pass a law that says your AR-15 must always send out its GPS position under continuous scrutiny by a form of AI — perhaps just a small pixel on a screen. If that pixel goes dark because you fell into your backyard pond with your gun while drunk, then the law might save your life. On the other hand, if you tamper with the transmitter then you will be arrested. In any event, if the signal stops, someone is sent out to investigate. That’s just the way the law reads. And of course, if the GPS signal is traveling in an urban area where it should not be — like mid-town Manhattan — then someone is likewise notified and actions are taken. I am not saying that anything like this is remotely likely or practical; I’m only saying that with AI, this scenario becomes a possibility.

But what about the negative aspects. Privacy, outside of your legal residence, will be a thing of the past. Once you leave the doorway, your movements, your visage, and your actions will be continually subject to AI monitoring. People may grouse but it will be accepted because of the security it will provide. Physical crime will be dramatically reduced; a criminal trial will consist of videos being stitched together by AI software, under the watchful eye of the defendant’s attorney, assisted by AI tools.

Will there be societal blow back? Of course. Vast numbers of entry level (and not so entry level) jobs will disappear. On the other hand, new jobs will be created. All of us will be press ganged into new jobs. We will spend our days being our own unpaid entry level clerks, creating and managing our digital accounts wherever we have dealings: from the store down on the corner, to our accounts up in our ‘cloud’. We will sit in front of our screens and an AI helper from behind the screen will focus on our entries, correcting us with visual examples, and speaking to us in clear understandable unaccented English. This AI helper will make sure we are doing our job accurately, and the information we enter is in the asked-for format. No more 800 numbers, waiting for a human helper, who against the odds will make all our waiting and frustration worthwhile.

Finally, there will be segments of our population who for many reasons will not adapt to this AI revolutionized society. Maybe some groups will have more difficulties than others; discrimination will have to be considered and fairly ameliorated. Opportunities should be guaranteed. This complicated process will continue for a long time, and likely will remain a challenge for our grandchildren and ‘their’ grandchildren as well. (Time will prevent most of my own ‘demographic’ from having to deal with these complicated negative consequences of the coming AI revolution. Being, as we are, (in a sense) ‘grandfathered’ in, our price for the short term will be small.)

WHO AM I TO MAKE ALL THESE PREDICTIONS?

At this point, you might think, what gives me the right to come up with all these forecasts and prognostications? It’s a fair question and I’ll try to answer it fairly. Of course, the easy answer is: this is what’s told to me by my own knowledge of things, and how, in my experience, these things tend to happen. But let me break down my reasons further. Let me start by telling you who I’m not, and at the same time, try to define myself by contrast.

I am not one of Grok’s designers and developers; I can’t tell you how Grok or any chatbot works. Yes, I can repeat words like ‘LLM’s and Large Language Models’ but they do not translate into anything understandable in my head. However, my ‘hands on’ experience goes back to the late 1970’s, and I *know* at the very bottom of any program, or set of instructions, any AI code must ultimately be translated into a series of machine language directions. I also *know* that anywhere along the track — from Seattle, where Grok reads my question; to Miami, where Grok finally displays its reply — and all points in between as Grok does its processing, there will be (perhaps) infinite opportunities for errors to occur, for the track to loop around itself endlessly or for the train itself to derail. This gives me a balancing built-in sense of caution that accompanies any optimism.

I’m not an academic; whose job is to think; teach and write about computers and software. Perhaps I can match the academic’s motivation. I am someone who feels that ‘learning’ is a good healthy activity for any retired person my age, (early 80’s). I enjoy learning like Sondra enjoys fast walking, and I hope it’s almost as beneficial. I’ve outlined my hopes with computers on Substack in August 2024, (and the link is in this sentence). As opposed to an academic, nothing I do with computers is theoretical. I only want my computer to make me more precise in my actions and more efficient in how I manage my life.

Lastly, I’m not a journalist, who writes, polishes and publishes his work for a living. For the reader, reliance on any journalist is risky; they may be more facile with their pen than knowledgable of their subject. In contrast, I’m simply your average joe, trying to get his computer to help organize and plan his life (calendar, email, text editor, etc.) Because I enjoy the challenge of writing, (encouraged by Substack), and because I can call upon my knowledge of computers; I will likely provide you with more useful information than journalists, including a sense of what AI may do for us in the future.

Although I am not many things; however, I am someone who has written and engineered complex software systems, marketing the same, (never with overwhelming success but obtaining a small set of loyal, appreciative and long-standing users). I am also someone who knows the human nervous system, including the brain. I have a working knowledge of its anatomy, physiology and organization. I have a sense of how it evolved. I know how it responds to various medications, to changes to its metabolism, and how it’s impacted by various hormones. The human nervous system has been the center of my career for decades. It was how I made my living. Then, 5 years ago I retired, left it behind and moved on to other things. Now I have ended up here, as my profile says, “on the interface between brain, memory and computer — looking at workarounds for problems of getting older“.

WHAT ABOUT THE DANGERS; THEY MUST BE REAL

I am saving my last comments to address the many qualms and concerns you have been reading and hearing about in newspapers, magazines and media of all type — AI, specifically chatbots, will end creativity; poetry and fiction will no longer be the province of being human. College essays and term papers of any kind will no longer be assigned and written. AI will do away with them all. I do not buy into any of this.

The creative impulse will be the same whether the artist (as sculptor) starts with a metal framework or a scaffolding courtesy of a chatbot, and then proceeds to add layers of clay, creating the sculpture — or whether the artist starts with a block of marble, compliments of the chatbot, and then like Michelangelo proceeds to free his David, chip by marble chip. In both cases, we will know that the finished product is the creative work of the artist. For decades, we have witnessed the entry, some say the unwanted inclusion, of technology into art. AI will be no different. Time alone will judge its value and permanence.

Likewise the impact of AI chatbots on college essays and term papers will be overblown. I doubt whether an AI chatbot will write a better paper than your average ‘essay mill operator’ (on college campuses), or produce better work than an average plagiarism-for-hire provider. However, there will be no comparison either in price or ease of accessibility. After a little exposure, following perhaps an introductory surprise, it will quickly become apparent what is generated by chatbots, and what is original.

In fact, I would bet money that right now there are developers beta testing AI software, designed to detect machine written essays. A teacher will feed a digital folder, containing all 50 essays from students, to the detection software. The essays will be machine read in an eighth of a second, and after another couple seconds or so, the detection software will deliver a probability estimate, whether the essay was machine written or not. Students would know and expect that if there was a strong probability — on the order of less than one in a hundred — that the paper originated from a chatbot; then the student would have to show evidence of his or her earlier interim work. This could be prior drafts, notes, searches, etc. Without that evidence, the paper could not go for grading. Ultimately, AI will not be a problem; unsurprisingly, it will help with grading essays.

SO HOW ABOUT THE FUTURE?

Bottom line; I remain optimistic about AI in our future, although I am somewhat dubious about chatbots, simply because they are capable of making such fat, consequential mistakes. Their premarket testing phase now seems over, and they seem complete; but I submit that we, their users, are still informally beta-testing their capabilities. Even though I’ve given up a dream of having a chatbot create for me a computer program that will play solitaire, according to my designs and instructions; nonetheless I am still trying to see if I can extend its capabilities. Like other users, I am trying to train my chatbot to start up with my computer system ‘specifics’ already preloaded. For necessary security reasons, chatbots are prevented from reading our files directly; such permissions cannot even be authorized by us, the users and owners. Since Grok has trouble storing any standing instructions, and must by design prioritizes fresh responses, it ‘powers on’ with somewhat of a tabula rasa, a clean memory state for the user to manipulate.

Right now, the present state of chatbots remind me of the university computer that we reportedly had at U.T. in Austin. Not that I ever even saw it! I was too busy with pre-med to think about computers.

In the summer of 1962, I remained in Austin for summer school and as a rising junior got a lowly job washing dishes (no money, free meals only) in the ‘Scottish Rite dorm’ at the edge of campus. (As I was writing this, I wasn’t even sure I remembered the dorm’s name, so I asked Grok if I was remembering accurately.)2

We were a team of four, responsible for washing the dishes after each meal. For this, we sat at a table in the kitchen and had a free meal before the dining room was served. We operated a long combination dish washer and dryer, containing a conveyer belt. We rotated through 4 positions: one to scrape the returned dishes and deliver them to the loader; who stood in the steam wearing a rubber apron and loaded the conveyer belt; one to take them hot and dry off the end of the belt; and finally one to carry the stacks of dishes to their appropriate cabinet spaces located throughout the kitchen. The first job struck me as ‘dirty’, the second one was ‘wet’, while the last one kept you permanently on the move allowing time to pass rather quickly. I always found the third one most difficult. It was boring, so it was easy for me to fall into a daydream-like state and lose attention. This job was physically the easiest but its ease was balanced by stress — needing to keep up concentration.

One of my washing mates was studying computer science and worked with the computer. He told me every morning, someone had to come in very early and load in the operating system. When they turned off the computer at night, any information in the computer’s memory was lost; so every morning someone was appointed to come in early, sit at a keyboard for an hour; and laboriously type in a string of alpha numeric codes, so the computer could operate. I thought with a shiver, “how boring that must be”. (Maybe we had just finished washing up lunch and I had come off the end of the conveyor, with difficulty managing to unload and stack the hot dishes before they clattered to the floor.)

By the time I had my first Radio Shack home computer, 15 years later, ‘Read Only Memory’ had been invented. Computers had evolved. System software did not die when the power was turned off. I assume chatbots will evolve as well. Perhaps I will be able to create specific text files and store them as a form of system modules with which to preload Grok for particular specified tasks. We’ll see if it leads somewhere.

As a psychiatrist, I cannot rule out that the recent shooter in the Manhattan office building did not have a brain disease resulting from high school football injuries, causing a chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). I suppose the autopsy will answer ‘yes’ or ‘no’. However, I *can* assure you that the odds are many thousand times greater that he actually suffered a malignant form of untreatable mental illness that never leaves behind clear cut brain evidence of injury. Nonetheless, his psychotic unreal *delusion* of brain disease will have, (with tragic irony), proven fatal to the shooter himself and four of his innocent victims. These serious cases of psychiatric disorder is extremely rare, but possible. In the course of my career, I can think of a few patients where this outcome could possibly occur. In this recent case, nothing conspiratorial will be involved, but HIPPA and fears of a lawsuit will likely prevent the psychiatric facts from seeing daylight.

Grok informed me:

By 1962, when you recall working there, the Scottish Rite Dorm (SRD) was a well-established residence for around 315 female students, known for its strict rules, including limited male visitor hours and curfews. In the early 1960s, SRD maintained a reputation for elegance and tradition, with features like chandeliers, oriental rugs, and a baby grand piano in its lavish parlor. It offered high-quality meals, unlike typical dorm food. It also employed young men as waiters and dishwashers, which may align with your memory of working there in the summer of 1962. Rules were strict, with a focus on creating a “wholesome, moral environment,” reflecting its original charter from 1920.

I was remembering correctly. It was the Scottish Rite dorm.

As usual, a thought provoking narrative. I look forward to his next intellectual adventure.